This webpage is about the history of the church from the earliest times, right through to the present day. It also gives information about the stained glass and furnishings, the churchyard, and recent archaeological excavations.

The Guide is also available in booklet form from the Tourist Information Centre in Lewes. At the present time it is free!

Clicking any superscript number will take you to the reference details

THE ST JOHN SUB CASTRO SITE

The history of the site upon which St John sub Castro Church stands is shrouded in the mists of time – however there are three key features of the site which can perhaps give us an indication of its early history.

Firstly, the layout of the land. The churchyard is sited on the top of a very distinct bluff of land, with steep scarps to the north (shown here), and to the east and west.

North scarp from Brook Street

Not only were there steep natural banks, but there is evidence from early images of the church that banks had been constructed on top of the scarp, which no doubt would have been surmounted by timber palisades. Thus the site had strong defensive capabilities.1

The River Ouse to the north west

Secondly, the site overlooked the river. Although this is constrained by flood banks today, it is likely that in earlier times the River Ouse was more estuarial in character and would have been navigable by sea-going ships.2 This would have allowed waterborne raiders to threaten the settlement at Lewes.

Thirdly, we know that there were two substantial mounds within the boundary of the churchyard site. The drawing shows the location of them in relation to both the first church and the present church. The mounds were probably of Romano-British origin, 3 although some suggest Bronze Age is possible. 3A

From a position on top of them one would have had a commanding view of the river and the country to the north.

The location of the two Romano-British (?) mounds (from a drawing by Andy Gammon)

These three factors combine to suggest the site may have had an important strategic defence value, possibly from a very early date.

A ROMAN CAMP?

It has been suggested that the site may have been occupied by Roman legionaries4: the terrace of houses at the west end of Lancaster Street is named The Fosse (Latin for ditch), because at the time the houses were built, it was believed that they were on the site of the southern defensive ditch of the supposed Roman camp.

The Fosse, at the west end of Lancaster Street

Roman finds on the site have been limited to a few coins discovered in the churchyard in the 19th century5

Roman coins found on the St John sub Castro site (Photos by Andy Gammon)

and a single piece of Roman flue tile discovered recently, so we cannot be certain of the extent of Roman occupation – however opinion suggests that there was a Roman route along St John’s Terrace and St John’s Hill towards Malling6.

The Roman forces withdrew from Britain during the 5th century, and this withdrawal was soon followed by the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons.7

THE CHRISTIANISATION OF SUSSEX

The Anglo-Saxons were pagans, and Sussex was one of the last strongholds of paganism. Although St Augustine arrived in Kent in 595AD, it wasn’t until St Wilfrid landed at Selsey in 680AD that the Christianisation of Sussex began.8

In order to establish a presence in a locality, it was not uncommon for early Christians to build a church close to an existing centre of pagan worship.

There is clear evidence of the presence of freshwater springs in the immediate vicinity of the northern scarp of St John’s churchyard – the Pells swimming pool is spring-fed, and old maps show that a stream at one time ran along where Brook Street is now, with a horse pond near the bottom of St John’s Hill.

Horse pond (from William Figg Map 1799 in SAS Library)

As pagan rituals often focussed on water, these freshwater springs may have provided a gathering point for such rituals.

One of the principal pagan feast days was the mid-summer solstice, and it may be significant that the patron saint of St John sub Castro is John the Baptist, whose Feast Day is 24th June.

It is possible therefore that the first church on the site dates from the 8th or early 9th centuries.9

THE VIKING THREAT

In the late 9th century, parts of Britain were threatened by Viking incursions, and to counter this threat King Alfred created a number of burhs, or fortified towns, in southern England.10

Lewes was one of those towns. It is generally accepted that the St John’s site was not within the circuit of the burh, but rather established as an outlying defensive position11.

John Elliot, writing in 1775, suggests that in the 9th century there was a causeway from the foot of St John’s in a straight line across the brooks to the river, and that the site of St John’s would have been fortified with mounds and oak palisades, “ as was the fashion in those times, to guard the pass into town against the plundering Danes who had then begun to infest the kingdom.” 12

CHURCHES WITHIN FORTIFICATIONS?

It is without doubt that King Alfred was a committed Christian, and Elliot suggests that Alfred may have built a church on this site for both defence and worship.13 The height of the blocked narrow lights at the top of the south elevation and close under the roof seems to denote that it was built for both purposes, and there are other instances of churches being used by the Anglo-Saxons as a defence against attacking forces.

St John sub Castro in 1786

(British Library ref XLII 22-g)

Elliot also notes that there was a “deep descent” of seven or eight steps down into the church14, and that herringbone style masonry was in evidence – both not uncommon features of Anglo-Saxon built churches.15

Further evidence as to the origins of the original church is offered by Pevsner, who refers to the triple arch doorway (now set in the outside wall of the present church), as being of Late Anglo-Saxon date.15A

These various factors combine to suggest that, even if a church had not already been established during the Christianisation of Sussex in the 8th or early 9th centuries, the existence of a church on the site before the Norman Conquest is not in doubt.

Fisher is strongly of the view that the name ‘St John in the Castle’ (as it appears in the 1190 document referred to below) is derived from its location within this fortified site, rather than from its relationship with the castle we know today.16

ST JOHN’S IN THE POSSESSION OF THE PRIORY

Thus far we have necessarily been in the realms of informed speculation regarding the early history of St John sub Castro church.

We might have hoped to find something more definite in the Domesday survey towards the end of the 11th century but surprisingly no churches are mentioned in connection with Lewes, even though we know for certain that St John’s existed, and possibly other churches too.17

The historical record concerning St John’s continues to be silent until 1121 when, along with most of the other Lewes churches, St John’s came into the possession of the Priory of St Pancras in Lewes, which, as the mother house in England of the Cluniac Order, must have had an enormous spiritual influence over the town until the Reformation.18

Priory of St Pancras, Lewes

(Drawn by Andy Gammon)

During that time the Priory, as Patrons, held the right to appoint the Rectors.

The name ‘St John in the Castle’ (or, as we have it, ‘St John sub Castro’) is first used in a document of 1190. Some say this is to distinguish it from the Priory Church at Southover, also dedicated to St John the Baptist – however Fisher’s suggestion above is also plausible.

MAGNUS THE ANCHORITE

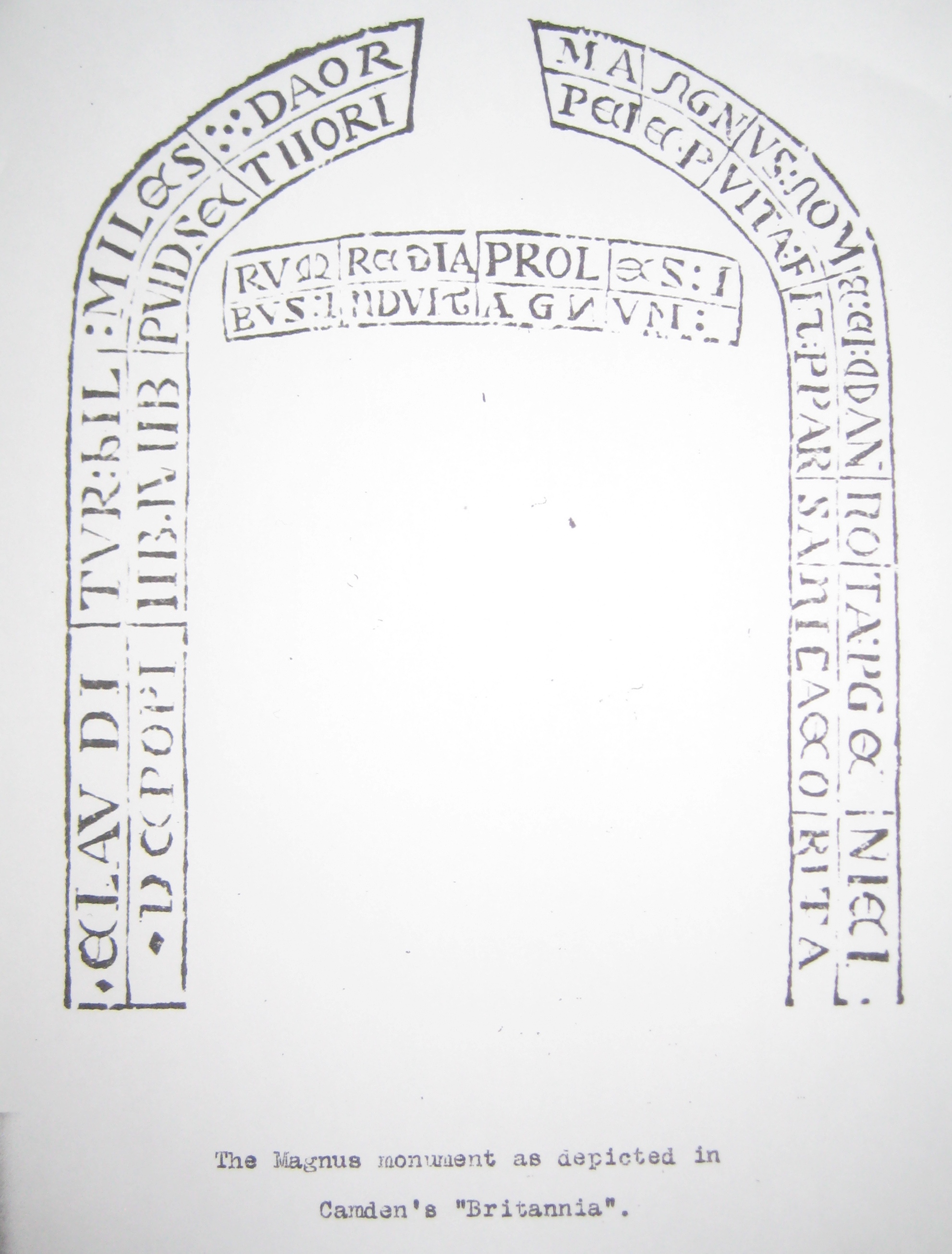

William Camden, writing his ‘Britannia’ in 1586, 19 tells us that the church had a mysterious resident in this early period (most likely in the 12th or 13th centuries).

He was a Danish prince named Magnus, known to us only from 15 inscribed stones which some have believed originally surrounded the access to the cell where he was walled up as an anchorite.

The cell was probably built on to the south side of the chancel.

Camden includes a drawing of the stones, and the Latin words on the inscription can be translated as follows:

“There enters this cell a warrior of Denmark’s Royal race: Magnus his name, mark of mighty lineage. Casting off his mightiness, he takes the lamb’s mildness, and to gain everlasting life becomes a lowly anchorite.”

The Magnus Inscription from Camden’s Britannia, 1586

Camden’s record is important because his is the only description of the church that we have before the chancel was pulled down in 1587. Camden would therefore have seen what we now call the Magnus monument in its original setting.

In his description of the chancel, he writes:

“in the walls thereof are engraven in arched worke certaine rude verses in an obsolete character which imply that one, Magnus, descended from Bloud roial of the Danes, embracing a solitary life, was there buried”

Although the drawing itself is thought to display a certain amount of artist’s licence, it could suggest that the lettering ran up and down the door jambs of the access to the anchorite’s cell.

On the other hand, an alternative suggestion favoured by some in the past is that the stones formed part of the 12th century chancel arch.

Both of these possible explanations however have their difficulties when examined in detail.

A more recent suggestion 19A regarding the original setting of the inscribed stones is that they formed part of a roundheaded tomb recess, in which Magnus was buried following his death – see this link:

12th -13th Century Tomb recesses

High-status recessed tombs of this type, bearing inscriptions relating the lives of their occupants, are well known from 12th and 13th century contexts.

This suggestion is supported by Camden’s account (noted above) of the stones in their original context. In it he clearly states that they were originally set within a wall (rather than forming part of a doorway), and that they marked a place of burial. This is echoed in 1826 by Stephen Glynne, who described them as ‘sepulchural stones’.

The Magnus monument today is set outside in the south wall of the present church. There have been various theories as to who Magnus was and why he should have given up arms and taken up a life of solitary prayer – but as yet it remains a mystery.

14TH – 15TH CENTURIES

By the 14th century Lewes was grossly overchurched, and in 1337 some of the churches, according to the Bishop of Chichester, were ‘diminished and impoverished’.20

For St John’s however, this may have been its most prosperous period – evidence points to it having had Minster (or Mother Church) status, with an enclosure encompassing a much larger area than the present churchyard. 20A There is also evidence to suggest that it provided the burial ground for several other churches in the town. 21

In the 14th or 15th centuries the church was enlarged. A small tower was built at the west end, perhaps with transepts extending from it, and a new chancel built.22

Records of Rectors go back as far as the 14th century, although the board in the church porch omits those before the Reformation. Of the medieval Rectors we know no more than their names – apart from one who achieved notoriety. About 1386 ‘William, parson of St John sub Castro’ was arrested with others for stealing a chalice from Hamsey Church and for highway robbery. For this crime he then received the king’s pardon! 23

TURBULENT TIMES

The Reformation brought major changes to the life and worship of St John’s along with the rest of Lewes, and some of the unwanted churches were closed. Among them St Mary-in-Foro, which stood at the top of St Mary’s Lane (now Station Street) was closed in 1544. It was then converted to the St John’s parsonage house, and its parish taken over by St John’s.24

The Dissolution of the Monasteries resulted in the destruction of the Priory of St Pancras in 1538, and soon after this the Patronage of St John’s passed for the next hundred years into the hands of the Sackvilles, who became later the Earls of Dorset.25

The period immediately after the Reformation was a time of much instability for all the churches, with the resurgence of Roman Catholicism (and the persecution of Protestants) under Queen Mary, and then the return of Protestantism (and the persecution of the Roman Catholics) under Queen Elizabeth.26 St John’s had no less than seven different Rectors between 1550 and 1560, no doubt of opposing religious persuasions. This was a time when many churches decayed or even fell into ruin, and St John’s was no exception. In 1586 Camden writes of St John’s “There remain still in the Towne six churches, amongst which, not farre from the Castle, there standeth one little one all desolate, beset with briars and brambles” 27

It sounds, however, as if steps were already being taken to improve things. In the same year the churchwardens wrote to the Bishop, “we want the Bible in the largest volume . . . And the walles of the churches beautified with sentences of Scripture.” 28They may or may not have been successful in this. The incumbent at this time was Thomas Underdowne, a ‘godly divine’ who was a leader of the Puritans in Sussex, and who pressed for greater Reformation of the Church of England. Along with others, he was suspended by the Archbishop of Canterbury from his duties for what were held to be extreme views, but then reinstated.29

DEMOLITION OF THE CHANCEL IN 1587

In 1587 some repair work was done on the nave. The chancel, however (for which the Reformers had little use), was pulled down, never to be rebuilt.30

The ragged ends of the demolished chancel walls and the infilled chancel arch show clearly in several of the images that we have of the church.

St John’s before 1779 by James Lambert

What does not show in these images however is the unfilled hollow which was left in the ground where the chancel had been. As noted previously, the nave was well below ground level, and we also know that the chancel was a further two steps down from the nave floor.31 This hollow, surprisingly, was left unfilled until 1779, and the grave slabs set into the floor of the chancel were left in place.32

Pending further research, it is thought possible that the below-ground walls of the chancel were not demolished at this time but left in place – ultimately to form the enclosing structure of the later Crofts family vaults. 32A

With the demolition of the chancel, the stones of the Magnus monument were scattered. Fortunately they were later collected up by John Rowe and other antiquarians. The first four stones were missing and had to be replaced and reinscribed. All the stones were then set in the external elevation of the south wall of the old nave.33

THE REPAIRS IN 1635

1635 saw a more comprehensive restoration project carried out and an inscribed stone tablet can now be seen built into the outside wall of the present church, above the Anglo-Saxon triple arched doorway. It reads “1635 Edward Middleton Henry Saman”. These were the churchwardens at the time, Edward Middleton living at Landport Farm.34

The 1635 inscribed stone tablet

However only 40 years later in 1675, we read that “The Staires in the bellfrey are out of repaire” and “the healing (roofing) and the covering of said church is in decay and wants repayrs” 35 a reminder that church maintenance is – and always has been – an ongoing problem!

THE ALTERATIONS IN 1779

In the mid-18th century a family came on to the scene who were to have a great impact on the whole future of St John’s.

John Crofts, a lawyer of Lincoln’s Inn, in 1741 acquired (as could be done in those days) the ‘advowson’ or patronage of the church.36 This means that he was able to present to the diocesan bishop for approval a person of his choice to be Rector of the church.

Thus it was that Daniel Le Pla, his wife’s brother, became Rector of St John’s.

Le Pla served for 34 years, and on his death in 1774, John Crofts put in his own son, Peter Guerin Crofts, as Rector.

Under Peter Guerin Crofts the Elder (as we must call him, to distinguish him from his son who also became Rector), major repairs and alterations took place in 1779.

Firstly, the subterranean nave floor was raised about four feet, to bring it up to ground level and to the level of the tower floor. The filling material needed for this came from the levelling of the easternmost of the two ancient mounds mentioned previously. At the same time, the “hollow of the old prostrate chancel” left when the chancel was demolished in 1587 was also filled.37

Secondly, the main entrance to the church was moved from the nave to the south elevation of the tower. The old triple arch Anglo-Saxon doorway was left in place and infilled. Inside its arch was placed, on end, a 13th century stone coffin lid found with a number of others during the alterations.

Other alterations included the installation of new pews, and the reduction in depth of the singing gallery at the west end of the nave from 15ft to 8.5 ft.38

Wakeham also records that the grave slabs removed from the chancel floor in 1779 were used either for steps up the bank at the west end, or paving the floor of the tower.39

This reference to ‘steps up the bank’ is important because it indicates that the defensive bank on the western side of the site, constructed in very early times, was still in existence in 1779 (James Lambert, 1780s, Burrell Collection, British Museum).

St John’s after 1779 by James Lambert

The 1779 alterations did not find universal favour – John Byng writing in 1788 noted that “the ancient church of St John has recently undergone a destructive reparation”, from which “brasses, stained glass and anything movable” suffered.40

The Rector, however, describes how he has ‘beautified’ the Church!

In 1784, after ten years as Rector, Peter Guerin Crofts died at the age of 39.

William Moreton followed, serving for 15 years until 1799.

A GROWING PARISH, AND THE END OF THE OLD CHURCH

Peter Guerin Crofts’ eldest son, only 10 years old when his father died, had an identical name. In 1799, fifteen years after his father’s death, Peter Guerin Crofts the Younger was himself appointed Rector at the age of 25, and only about a year after his ordination. He was to remain 48 years, the longest of any Rector. He married into the wealthy Campion family of Danny, near Hurstpierpoint, and eventually bought Malling House (the present Sussex Police Headquarters) as his Rectory.

Up until the late 1700s, the church had stood in an isolated position near the former town wall, with open fields and only a few houses and the Lewes House of Correction (built in 1793), between it and the town.

But there now came a period of unparalleled growth in the town of Lewes as a whole, and especially in St John’s Parish.

In the area running outwards from Market Street and Fisher Street the ‘New Town’ was built. This included the development of roads such as Sun Street, Abinger Place and New Road41 – and the population of the parish rose from a mere 659 in 1801 to 2300 in 1831.42

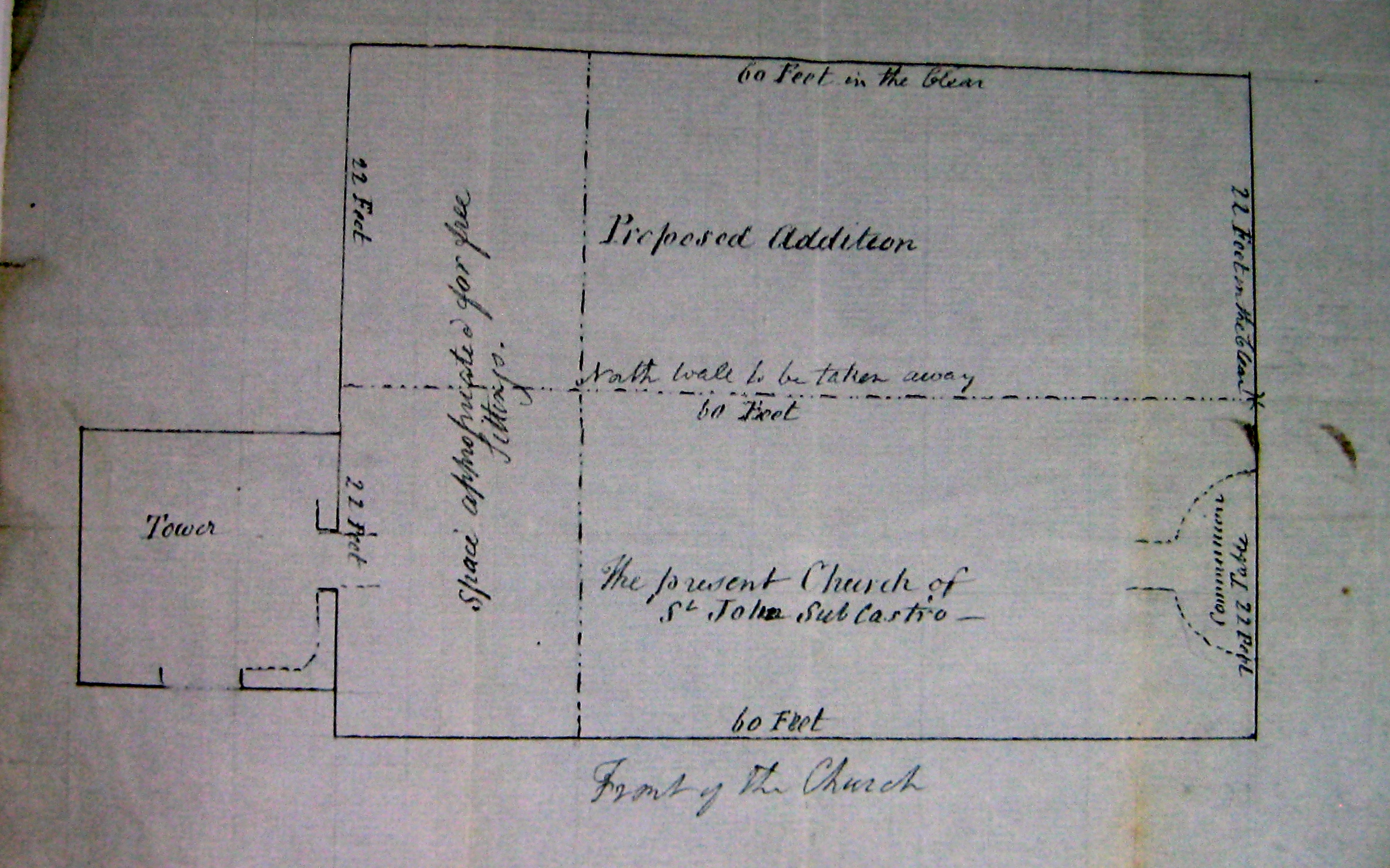

St John’s Church, however, only seated 260 people, and must soon have become overcrowded. Under Revd Peter Guerin Crofts, plans were drawn up in 1818 to enlarge the church and provide an extra 180 seats at an estimated cost of £750.43

The Enlargement plan for the old church (Lambeth Palace Library)

Nothing came of this however, and by the mid 1830s it became clear that a more radical solution was needed – Revd Crofts therefore launched an appeal in the following terms:

“…..The parish of St John contains according to the last census, 2,625 inhabitants, almost entirely Mechanics or Labourers – and the population is rapidly increasing…..To supply this glaring want of Church Accommodation, it is proposed to take down the present church and to erect a new one to contain 1000 Sittings – 600 at least to be free…..” 44

The proposed new church (Lambeth Palace Library)

And so, in May 1839, in what we should regard as an act of appalling vandalism, the 800 year old church was ‘taken down’, 45 and preparations for the construction of the new church started on a site several metres to the south.

THE INTERIOR OF THE OLD CHURCH

So far, apart from Camden’s account in 1586, the records have yielded little information about what the church looked like inside – however we do have a ground plan of the church by William Figg dated 1816.46

This shows a nave length of 61ft and a width of 24ft – a length to width ratio of 2.5 which is within the range of typical of Anglo-Saxon proportions.47

Plan of church in 1816 by William Figg (SAS Library)

A list of pew holders at that time48 makes it clear that there would have been little room left in the church for people in poorer circumstances – an unsatisfactory situation fortunately remedied when the new church was built.

Rouse remarks in 1825 that the ancient appearance of the church was “much diminished by the introduction of lime, whiting, and square wooden window frames”.49

Glynne’s opinion in 1826 was no more complimentary – he writes:

“St John’s Church is at present a very mean structure, having been much curtailed of its original dimensions and experienced many tasteless modern alterations and mutilations. The interior contains nothing remarkable. The windows are all modern and most wretched compositions.” 50

Notwithstanding these rather negative opinions, there was nevertheless hanging in the church over the Communion Table, a large painting in a fine frame having as its subject ‘Christ Blessing the Children’.

THE LEVELLING OF THE MOUND

The proposed new church, seating over 1000 people, was much larger than any other Anglican church in the town, and owing to the limitations of the site it had to be oriented on a north-south axis rather than on the more usual east-west.

It was therefore necessary to level the ancient burial mound referred to earlier, which occupied a major part of the area available for the new church.

We have an account of the levelling of the mound which appeared in the Sussex Agricultural Express on 25th May 1839:

“ . . . they came to large piles chalk, so arranged as to afford spaces . . . for a human skeleton each, which were protected by a wall of chalk and filled up with ditch clay; presently they came to what the workmen termed an ‘oven’, or a rude construction of a steined vault ; and when they reached the centre of the crown of the Mount they exposed a circle of burnt earth, of two rods diameter, around the sides of which we were a few burnt human bones and a large quantity of boars’ and other animal bones also burnt. On the east side an urn of baked clay was found, also a spearhead or iron weapon; showing that the Mount was an ancient British barrow, and that long before Christianity was introduced into England, St John’s church yard was a scite for Druidical sepulchres.” 51

THE BUILDING OF THE NEW CHURCH

It should be noted that for liturgical reasons, churches were usually built on an east-west axis, with the altar at the east end. However as has been mentioned previously, and due to the limitations of the site, the new church had to be built on a north-south axis.

To avoid confusion (for which there is much scope!) the more usual liturgical compass points have been used when describing locations relating to the present church.

The architect and builder for the new church was George Cheesman from Brighton. The corner-stone was laid in June 1839,52 and the church was consecrated by the Bishop of Chichester one year later, on 3 June 1840.53

The cost of £3,300 had been fully paid for by that time – a remarkable achievement, especially since (as a board in the porch records) three quarters of this came from voluntary local contributions. An attractive feature, mentioned in the sermon at the consecration, was that over half the seats in the church were free (no pew rents being charged), and, unusually for those days, many of these free seats for ‘lowly occupants’ were in the middle of the nave.54

What of the external appearance of the new church? Cheesman would have been familiar with St Peter’s in Brighton (1824-8) – a notable Gothic Revival church designed by Charles Barry – and there are indeed some resonances of style between the west fronts of St John’s and St Peter’s. However, Cheesman sought to reflect the castle in his design for St John’s by including turrets and castellations.

Unfortunately this did not find universal favour – Gideon Mantell declared that it was “an unsightly edifice which I fain would have passed unnoticed” 55 and Mark Anthony Lower accused the bad taste of the authorities for such a “hybrid structure, half castle, half barn!” 56

An early picture of the present church

Revd Peter Guerin Crofts the Younger retired in 1847, to be followed by George Hall, about whom little has yet been researched, and Robert Grignon.

A measure of the strength of St John’s in this period is provided by the national Religious Census of 1851 (the only one ever taken) in which the average Sunday attendance at the church is it given as 800, which was much the largest attendance of any of the Lewes churches.

RELICS FROM THE OLD CHURCH INCORPORATED IN THE NEW

Some relics from the old church were incorporated in the new structure.

The Anglo-Saxon triple arch doorway

The doorway has been much repaired, but sufficient remains to prove that it possesses the same general character as the early portion of Sompting church and other churches which are regarded as specimens of Anglo-Saxon architecture. 57

One of the earliest pictures we have of it is that by James Lambert, 57A which pre-dates the 1779 alterations and is shown on this link:

When the entrance to the church was moved to the south elevation of the tower in 1779, the old doorway remained in position but was blocked up – the infill incorporating one of several ancient coffin lids discovered at that time.

The church was demolished in 1839, and the doorway built into the east wall of the north vestry of the new church – however without the six courses of stonework shown in Lambert’s picture.

When this vestry was enlarged in 1883 to accommodate the organ, it was relocated again – this time to the equivalent wall of the enlarged vestry, which is where we see it today.

The triple-arch Saxon doorway

Above it is the 1635 inscribed stone tablet, and within the arch is set the original old coffin lid.

A great deal has been written about the details of this doorway, and further information about it can be found in the references details. 58

The Magnus Monument

The Magnus Monument and its origins have been referred to previously, and it can clearly be seen in all images of the old church.59

When the old church was finally demolished in 1839, the inscribed Magnus stones and associated coffin lid were nearly discarded for the second time in their history.

They were however rescued by Mark Anthony Lower and built into the east wall of the south vestry of the new church.

When this vestry was enlarged (probably in 1883), the monument was relocated again – this time in the south wall of the enlarged vestry, which is where we see it today.

The Magnus Monument

A great deal has been written about the possible circumstances of Magnus and the details of the inscription – further information about these can be found in some of the references.60

The Bells

The bells of the church were recast in 1724 and are interesting as being the work of a known itinerant bell founder, John Waylett, who can be traced through the county between the years 1714 and 1727, setting up his furnace in any neighbourhood where he could command orders. His method was to call on the Rector and ask if any repairs were wanted; and if a bell was cracked or if a new one was desired, he would dig a mould in a field nearby, build a fire, collect his metal, and perform that task on the spot. There are more than 40 of his bells in Sussex.61

The Bells

St John’s at that time possessed three small bells – two were broken and the third was much cracked. These he re-cast and inscribed on them:

“JOHN WAYLETT MADE ME 1724”

All three were re-hung in the tower of the new church – however the 3rd of the original bells had to be replaced in 1886 and is inscribed:

“MEARS & STAINBANK FOUNDERS LONDON 1886 THE REVD A P PERFECT RECTOR

I WAS PLACED HERE IN THE JUBILEE YEAR OF VICTORIA OUR QUEEN BY SUBSCRIPTIONS COLLECTED BY WM BANKS & JOSEPH KING”

The bells were originally hung in the new church for swing chiming, but in more recent years they were fitted with Ellacombe type chime hammers. The bells are now only used occasionally.

The treble and the 2nd are listed for preservation by the Church Buildings Council.

The Font

The old font, now sited in the porch, is something of an enigma.

The unusual shape of the bowl, with flat sides to the back right and left, makes it suitable either for fitting into a corner or against a wall.

The pedestal has eight sides, only some of which are carved with minature pointed arches, suggesting it was designed to be viewed from one side only.

As to date, some think the bowl post Anglo-Saxon and the pedestal 15th century – others have dated the entire font to the 15th century.62

As to date, some think the bowl post Anglo-Saxon and the pedestal 15th century – others have dated the entire font to the 15th century.62

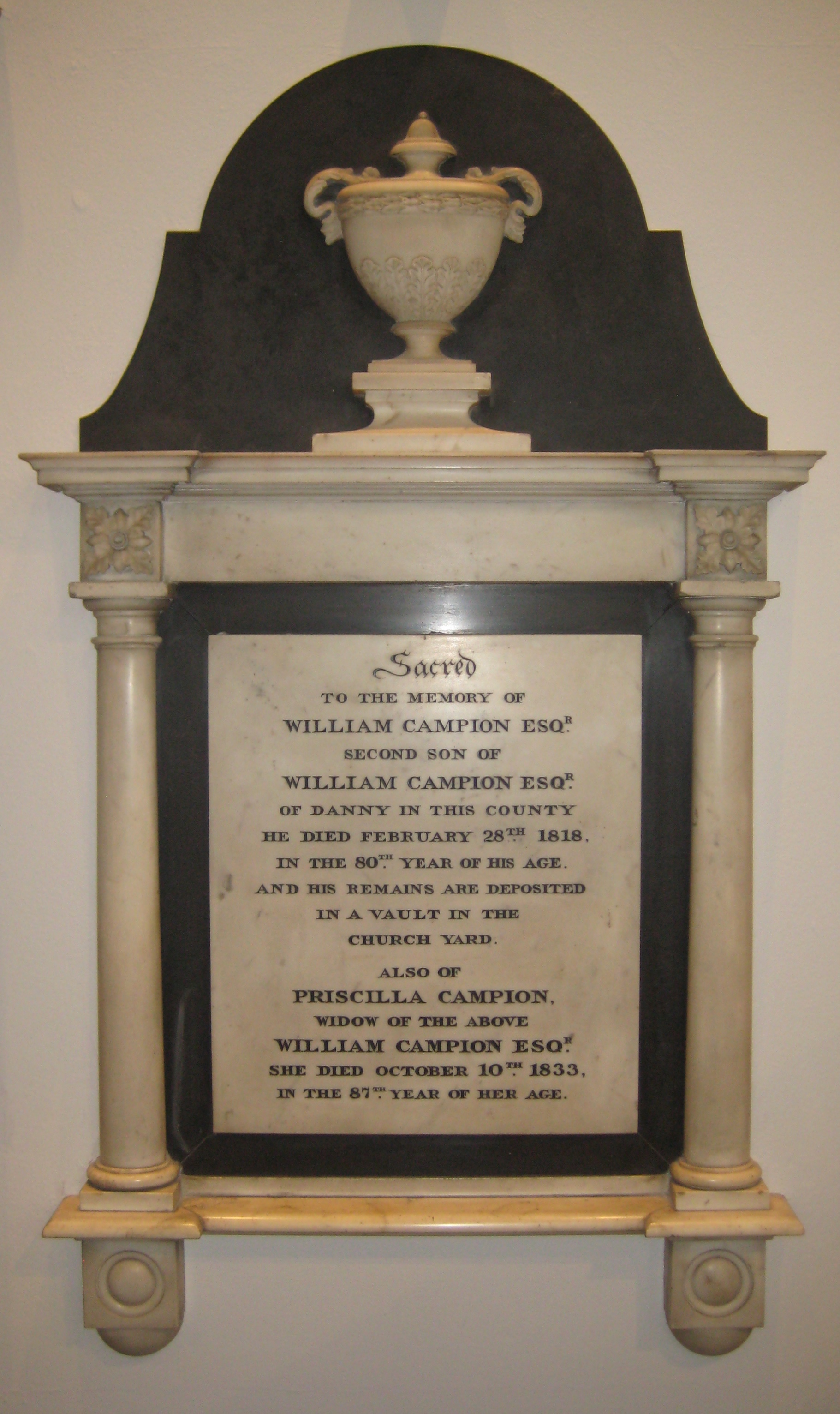

The Memorials

Several of the wall monuments to the Crofts and their close family members were transferred from the old church to the chancel of the new church. The one shown here commemorates William and Priscilla Campion, whose daughter Harriet was Peter Guerin Crofts the Younger’s first wife. She died in 1813, within a year of their marriage.

Several of the Crofts’ family had been buried beneath the floor of the old church,63 and it was presumably when the old church was demolished that their remains were removed to the new family vault on the site of the chancel of the old church. A paved platform marks the position of the vault in the churchyard, and Peter Guerin the Younger was buried there when he died in 1859.

Railings which once surrounded the vault were removed in the Second World War.

Crofts family vaults

The Frans Floris painting

This large painting, in a fine frame surmounted by the Crofts family crest, has as its subject Matthew Ch19 v13-15: ‘Christ Blessing the Children’.

The artist was not known until 2004, when it was identified as coming from the workshop of the Flemish painter Frans Floris, who lived and worked in Antwerp. The painting dates from the 1550s.

The artist was not known until 2004, when it was identified as coming from the workshop of the Flemish painter Frans Floris, who lived and worked in Antwerp. The painting dates from the 1550s.

At that time Floris had adopted the ‘workshop’ concept of production. This was based on a division between the ‘invention’ of the painting (deciding on the subject matter and the composition for example) – and the actual execution of it.

Thus Floris would have created the painting in conceptual terms, painted some of it, and then entrusted parts of the execution to trained assistants.

This is borne out by the discovery in 2012 of the monogram FFF ET IV on the painting. This is the ‘signature’ which Frans Floris used, and abbreviates ‘Frans Floris Fecit et Invenit’ – literally ‘Frans Floris made it and designed it’.63A

You can see the monogram in the photo below.

Frans Floris Monogram FFF ET IV

The painting was one of a number of gifts made to the church by John Crofts in 1751, who seems to have come into possession of it as executor to Mrs Powlett of Halnaker near Chichester.

It has been said that her husband, Captain Powlett, gained it as a prize in a naval engagement.64 However, we now know that Powlett was a Captain in the Horse Grenadiers, so the connection with a naval engagement is not immediately apparent! Research continues . . .

The painting hung over the Communion Table in the old church,65 and it now hangs high up on the wall at the back of the present church.

THE ALTERATIONS IN 1883 AND 1903

1868 saw the arrival of Revd Arthur Pearson Perfect, who exercised a long and distinguished ministry at St John’s until 1910 – a total of 42 years. He was described as ‘evidently a model parish priest’ working in ‘the largest and also the poorest parish in Lewes’.66

He was responsible for some significant changes to the church building – most notably the 1883 alterations, considered necessary at the time owing to “ . . said church being inadequate and devoid of architectural character.” 67

Under architect Philip Currey, a high level apse was built on to the chancel, with three stained-glass windows by the celebrated artist Henry Holiday. Holiday was a friend of Burne-Jones, one of the pioneers in the recovery of medieval methods of stained glass manufacture, and his influence can be seen in Holiday’s work.

At the same time as the addition of the apse, several other alterations were made. The west gallery was removed and the organ which had stood there was moved to a new organ chamber in the chancel, where it is today; the Frans Floris painting which had been hanging on the wall of the chancel was moved to the west wall of the nave where the gallery had been; the vestries on either side of the chancel were enlarged, and the box pews were replaced by open benches.

These 1883 alterations may have been inspired in part by the Oxford Movement, which sought to turn the clock back to pre-Reformation times, with its greater emphasis on the High Anglican style of worship and the importance of the sacrament of Holy Communion.

Further stained glass was introduced into the church between 1883 and 1910, in the north and the south aisles.

When the church was built in 1840 it had a flat ceiling, level with the underside of the main beams. In 1903, this became unsafe and discoloured and it was removed to expose the roof structure and the painted panels that we know today.68 We don’t know how the panels were decorated in 1903, but some will remember the 1960s décor – memorably described by one incumbent in his inaugural address as resembling a Battenburg cake!

The 1960s Battenburg ceiling!

This was not universally acclaimed – certainly not in recent years anyway – and in 2015 the panels were decorated in a much less controversial style for the times.

Revd Perfect died ‘in harness’ in 1910, and a stained glass window in the north aisle is dedicated to him.

THE WORLD WARS

Arthur Pearson Perfect was followed by Frederic John Poole, but his ministry was tragically brought to an end in 1923 following a fatal accident in the town when returning home from a service of Holy Communion. Revd Poole nevertheless had led the church through what must have been very difficult times between 1914 and 1918. The Great War saw many casualties from the St John’s parish, and a Wall Tablet and wrought iron screen were dedicated to them on 1st November 1921, bearing the epitaph:

“Live thou for England, we for England died”

War Memorials

There are 69 men listed on the First World War Memorial.

During the Second World War it was reported that between 140 and 150 parishioners were serving in various branches of the Forces, and there are several reports of the choir being depleted due to men away on active service.

Many lives were again lost from the parish – there are 36 names on the Second World War Memorial.

LANDPORT – A GREAT EXPANSION OF THE PARISH

Revd Frederic Poole was followed by Revd Herbert Langhorne.

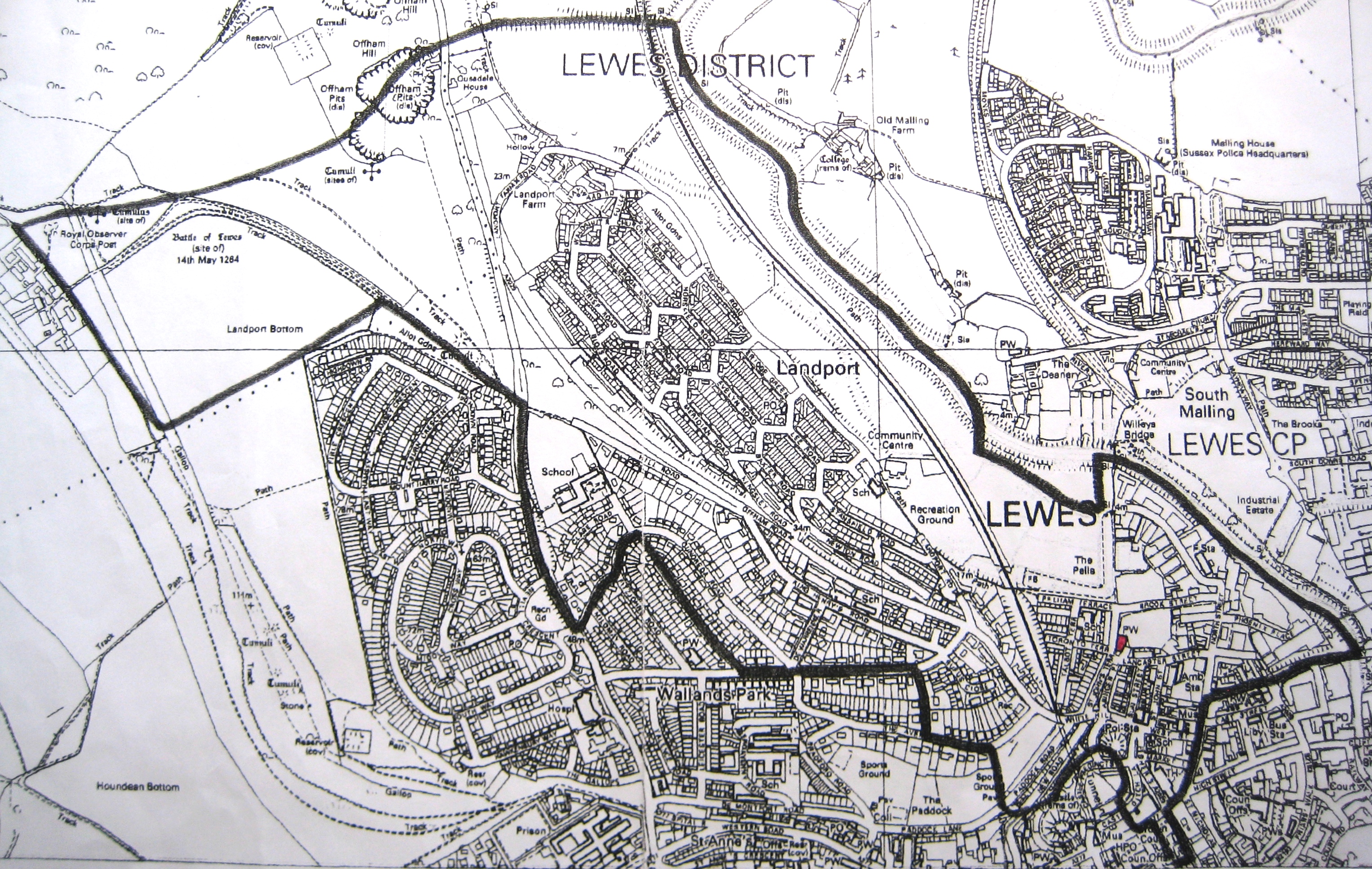

In 1938, a start was being made on the development of the Landport Estate. All of this lay within the St John’s Parish, and by 1939 it was becoming clear to Revd Langhorne that he would need extra clergy help to cope with the increase in what was already a very large parish.

Map of St John’s Parish (Crown copyright licence no. 100002215)

Following a meeting with the Bishop, it was evident that such help would not be possible, and this difficult situation persisted for a number of years.

By 1949 the problem was no less acute – the Rector referring to the difficulty experienced in working the two parishes single-handed. The Landport Estate had therefore at that time been acknowledged as a separate parish – although it later reverted to a single parish again.

At the end of 1951, Revd Langhorne resigned having served St John’s for 27 challenging years.

Difficult times continued, with the vacancy at St John’s not being quickly filled. In 1954 St John’s was united with St Thomas at Cliffe and All Saints, because St John’s had become unable to be financially independent.

In 1955, Revd A.P. Cameron was appointed Priest in Charge of the three parishes. For this to be successful, Revd Cameron needed a curate to help him, but because at that time there was no suitable clergy house available to offer a prospective curate, it proved impossible to attract the right person.

Revd Cameron, evidently under a great deal of pressure, resigned in 1958.

MORE SETTLED TIMES

Revd John Williams followed and by this time the clergy housing difficulties had been resolved, and Revd Williams was able to provide a stable and much valued ministry until 1965.

A period of strong congregation growth then followed between 1965 and 1974 under the inspirational leadership of Revd Michael Loughton.

After two further short incumbencies, there followed a long period of stable and fruitful parish life lasting 22 years under Revd Robert Bell, who retired in 2000. Much was achieved towards strengthening parish life during this period, and apart from the normal run of necessary church repairs and minor works, an important alteration to the church during this time was to create a much needed kitchen and toilet in one of the stair wells.

This was important because it enabled refreshments to be served after services, and this in turn made a huge contribution to church life by enabling community outreach to develop, and by our being able to welcome newcomers – and this of course continues to the present day.

Revd Martin Sully was appointed in 2001, and remained until 2009. There were several important initiatives during this period – the installation of a toilet for the disabled; improved kitchen facilities; a new monthly service held in the Pells School on Landport; lunchtime concerts; and a weekly parent and toddler group called Acorns, meeting in newly created space at the back of the church.

Revd Sully was strongly supported during this period by Revd Dick Field, who had recently retired into the parish. Indeed, Revd Field has continued to provide invaluable support to successive incumbents right through to the present day.

BATTLING WITH THE BUILDING

Although major structural repairs were carried out around the time of the 150th anniversary of the present church in 1990, the building continued to deteriorate.

The congregation by this time was dwindling, becoming older, and was unable to maintain such a large building.

In 2010 the parish was joined with St Michael’s South Malling under Revd Al Pickering, who successfully led us through challenging times when the very future of St John’s, with a small congregation and a dilapidated building, was in doubt.

In 2013 substantial funding was secured from Historic England and Chichester Diocese to carry out Phase 1 of a major programme of structural repairs. This included the renewal of the Tower, Nave and Sanctuary roofs, repairs to masonry, and essential re-wiring.

The renewal of the Nave roof (Photo by Andy Burrell)

THE CREATION OF TRINITY CHURCH LEWES

In 2014 Revd Steve Daughtery, Rector of St John the Baptist Church Southover, put forward an exciting plan to join his church with St John sub Castro and St Michael’s South Malling to create a new church and parish, to be called ‘TRINITY Church’.

He also proposed a complete remodelling of the interior of St John sub Castro church so that it could be used more effectively for both services and community use.

In 2015 this plan was approved by Chichester Diocese, together with substantial help from them towards funding, and the remodelling of the interior started.

Renewing the Nave floor (photo by Geoffrey Williams)

At about the same time funding was secured from the Heritage Lottery Fund to carry out Phase 2 of the structural repair programme.

Remodelling continued into 2017, and both this and the repair programme progressed in parallel to completion at the end of 2017.

The result is the church you see today, complete with flexible worship space, community cafe, children’s play room, additional meeting rooms and the TRINITY administrative centre.

The remodelled chancel area

The photo below shows our community Café12/31, which derives its name from a verse in the Bible – Mark 12:31 ‘Love your neighbour’.

The West end of the Nave

THE LAMB AND FLAG WEATHERVANE

One of the most visible features of the repair programme was the repair and re-gilding of the Lamb and Flag weathervane mounted on top of the tower – an icon heavy with symbolism amongst the surrounding community.

The Lamb is a symbol of Christ, recalling the words of John the Baptist:

“Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world”

(KJV John1:29).

The Flag is a symbol of Christ’s victory over death in his Resurrection.

The newly-gilded Lamb and Flag weathervane

TRINITY St John’s is now a vibrant part of the local community and the whole of Lewes. Like the other Lewes churches, it has survived many ups and downs over the centuries. It still stands firm, dominating its part of the town – a visible reminder of Jesus Christ who never changes, even when all else changes.

“Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today, and for ever”

(NIV Hebrews 13:8)

TRINITY St John’s is part of TRINITY Church Lewes, together with TRINITY Southover and TRINITY South Malling

TRINITY is a vibrant and outward-looking Anglican church meeting across 3 locations and 6 congregations in Lewes, with a vision to see lives transformed by the love of Christ. You can find out more about our community right here at St John’s, or you can visit the TRINITY website at:

We hope you will pay us a visit soon, and we look forward to meeting you!

Revd Steve Daughtery, Vicar of Trinity Church, Lewes

Information about the stained glass, church furnishings, churchyard graves and memorials, Church Schools, the Church Hall, and recent archaeological finds, can be found in the following pages of this guide.

STAINED GLASS WINDOWS

Apse

The left hand window is dedicated to George Peter Bacon (1806-1878), and represents St Peter on the left holding the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven (Matthew Ch16 v13-19), and St John the Baptist on the right: ‘The Kingdom of Heaven is at hand’ (Matthew Ch3 v1-3).

George Peter Bacon

The centre window is dedicated to Charles Moore Luckraft, Lt., HMS ‘Cormorant’ (1850-1882), and shows Jesus on the left walking on the water: ‘It is I, be not afraid’ (Matthew Ch14 v25-32), and on the right

Jesus the Good Shepherd: ‘I am the good shepherd’ ( John Ch10 v11).

Charles Moore Luckraft

The right hand window is dedicated to George Mackenzie Bacon M.D. (1835-1883) and Walter Charles Bacon (1836-1883), and represents St Luke on the left: ‘To live is Christ’ (Philippians Ch1 v21-24), and St Paul on the right: ‘ To die is gain’ (Philippians Ch1 v21-24).

George Mackenzie and Walter Charles Bacon

The designs appear to have been adapted to suit the setting from cartoons by the artist, Henry Holiday (1839-1927), and the golden-haired angels at the bottom of the panels are a ‘trademark’ of his work.

The windows were made by James Powell & Sons, Whitefriars Glassworks, London.

North Aisle

In the north aisle, the pair below are in memory of Henry James Gibbins (1803-1877). They draw from the parable of the talents, recorded in Matthew’s Gospel, Ch 25 v14 – 30.

Curiously, the parable appears to have been misunderstood by the designer of the window, because the presence of the spade clearly identifies the subject of the window as being the kneeling figure of the servant who buried his one talent in the earth and was roundly condemned by his master for doing so. Thus the text “Well done thou good and faithful servant” would appear to be entirely inappropriate!

The windows were made by Savell, Albany.

Henry James Gibbins

The pair below are in memory of Louise Victoire Alphonsine Gibbins (1809-1894) wife of Henry James Gibbins. Across the top of the windows is a quotation from St Mark’s Gospel, Ch14 v8:

‘She hath done what she could’ (King James version).

The window shows a female saint, richly robed, offering food to needy people. These windows were also made by Savell, Albany.

Louise Victoire Alphonsine Gibbins

The pair below are dedicated to the “Revd Arthur Pearson Perfect, (1839-1910) Rector for 42 years: dedicated by his many friends, 1910”.

The windows show the Virgin Mary with Jesus holding a lily, both richly robed, and St Elizabeth holding an open book, with John the Baptist as a boy wearing a camel hair skin and holding a wooden staff.

These windows were likely to have been designed by Charles Eamer Kempe, a prolific stained glass artist, born in Sussex. They were made by the firm of Walter Tower.

Revd Arthur Pearson Perfect Memorial Window

South Aisle

The windows in the south aisle are dedicated to Adele Alphonsine Holman (1854-1885) and show two female saints, representing Faith and Hope.

On the left, Faith is dressed in a green robe and holding a cross. Green was often used as a symbol of new life, and in particular the triumph of life over death – just as the green in spring overcomes winter.

This then links with the symbolism of the Cross – which points to Christ’s triumph over death, and the new life in Christ which Faith can offer.

On the right, Hope is dressed in a blue robe and holding an anchor.

Blue was traditionally the colour of the sky, and it was used to symbolise heavenly love, and the anchor was an ancient symbol of safety, and so of hope for the future.

In the Christian tradition these two ideas link together to suggest the hope of salvation and of eternal life, within the heavenly love of Christ.

At the top of the window, on the left are the letters IHS which represent Jesus in Greek. On the right are the letters XP – often called the Chi Rho – which represent Christ in Greek.

The two together are often referred to as one of the Sacred Monograms.

The window was designed by Savell & Young, Albany.

Adele Alphonsine Holman

ORGAN

We have no information about any organ in the old church, but we do know that after the Consecration Service for the new church in 1840, a collection at the door realised £51 (about £5,000 today).69 This was set aside for the purchase of an organ, and this would have been installed in the original west gallery.

In 1883, the west gallery was removed, and a new organ (possibly by Bishop & Son) was installed in a new organ chamber on the north side of the altered chancel.

This organ was rebuilt in the 1927 by Morgan and Smith of Brighton, and is substantially the same tubular- pneumatic organ that we have today.70

In recent years it has been the subject of complete re-leathering, together with stop changes.

The St John sub Castro Organ

EAGLE LECTERN

The eagle lectern is dedicated to Lt Charles Moore Luckraft RN (1850-1882) who was killed whilst serving on HMS ‘Cormorant’ in the South Pacific in 1882.

HMS ‘Cormorant’ was an ‘Osprey’ class sloop, whose purpose at that time was to maintain British naval dominance through trade protection, anti-slavery and surveying. She served on the Australia and Pacific Stations during the late 1870s and 1880s.71

The circumstances surrounding the death of Lt Luckraft are not altogether clear, but he appears to have been killed in a dispute with the natives on Espiritu Santo Island in the New Hebrides.72

Eagle lectern

ST JOHN’S CHURCHYARD

Primroses and bluebells

“The breezy call of incense breathing morn,

The swallow twittering from the straw-built shed,

The cock’s shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed”

(Gray’s Elegy)

St John’s churchyard is a delightful green space of over 2 acres. It is well hidden, and many people don’t even know it is there.

It has been a burial ground for centuries but it is closed for that purpose now, being managed expressly for the purposes of nature conservation.

Its surrounding flint walls and the site of the ancient church within them were listed Grade II in 1970.

The churchyard used to be smaller than it is now, the older part being that near the present church. It was extended to its present size in 1866.73

If you visit the churchyard, look for the following:

The Crofts family vaults

Crofts family vaults

These are beneath the grave slabs shown in this photograph.

An inscription on the western edging stone reads:

“THE SITE OF THE CHANCEL OF THE OLD CHURCH”.

It has been assumed in the past that ‘the chancel of the old church’ referred to here is the chancel that was pulled down in 1587 – thus suggesting that the vaults lie within the footprint of this original chancel. 74

If this is correct, the nave and tower would have extended westwards from this kerbstone in accordance with the measurements shown on William Figg’s drawing in 1816.

However, when we measure this out on site today, we find that the footprint of the tower extends beyond the top of the St John’s Hill bank, which is clearly impossible. A check of the 1870 and 1910 Ordnance Survey maps shows no evidence of the bank being cut back when St John’s Hill was constructed in the 1890s.

Furthermore, we have an image of the church looking down St John’s Hill before the houses were built in the 1890s, and the track (as it was then) looks in a very similar position relative to the church as the road does today – suggesting that the bank was not cut back when the church was demolished in 1839.

An early picture of the present church

In order to overcome this apparent discrepancy, an alternative view is that ‘the chancel’ referred to in the inscription was in fact the area at the east end of the nave which accommodated the Communion Table shown on Figg’s drawing, and which in effect became the ‘new’ chancel after the demolition of the old one in 1587.

This would move the previously assumed footprint of the church some 12ft (3.7m) eastwards, bringing it inside the top of the bank, thus overcoming the problem referred to above.

Other considerations support this view. In particular, the burial record for grave no. 754 dated 15th August 1737 states that this burial is ‘in a tomb near ye church porch’. Until 1779, the church porch was in the position shown on the James Lambert drawing:

St John’s before 1779 by James Lambert

This drawing shows a cluster of chest tombs near the porch, and it is most likely that grave no. 754, identifiable today and shown below, is one of those. Indeed, there are others close to it which are known to have existed before 1779.

Grave no. 754

As grave no. 754 is ‘near the church porch’, relocating the footprint of the the church 12ft eastwards as suggested above will better fit the relationship between the grave and the porch as described in the burial register.

Further research on this is needed, and the results will be added to this website when they become available.

The Painters Lambert

James Lambert Snr (1725-1788) and his nephew James Lambert Jnr (1741-1799) were landscape painters of considerable repute who lived in Lewes. In later years, they worked in partnership, producing more than 600 paintings and drawings together. Their subjects included many churches, and were of particular value because they were principally intended for historical record and required to be ‘precise’ as opposed to ‘artistic’.

Both James Lambert Snr. and Jnr died in the Cliffe, but as the church there had no graveyard, they were buried at St John sub Castro. Their memorials are now on the outer wall of the apse, but sadly almost illegible now. They read: “Mr James Lambert, Landscape Painter, late of the Cliffe, died 7th December 1788 aged 63 years, his affectionate nephew erects this” and “Mr James Lambert, Herald and Landscape Painter, late of the Cliffe, died March 22nd 1799. aged 57 years. His surviving friend erects this.” 75

Memorial to James Lambert Snr

Thomas Blunt

A notable chest tomb is that of Thomas Blunt, an inhabitant of the Parish and a benefactor to the Town. He died in September 1611. He was a member of the Society of Twelve, which was a fellowship of the most wealthy and influential townsmen from which the High Constable was elected. Although always described as a barber, it is evident from the above qualifications that he was a person of means and influence. Very probably he was one of the barber surgeons who practised in those days. He bequeathed a silver gilt cup and cover to the High Constable and Society of Twelve which is still used today for municipal celebrations.

By his will dated 26 August 1611, ‘£1 yearly to be paid to the poor of the parish of St. John-under-the-Castle’, and still today there is money available from Blunt’s Charity for the relief of the needy in the parish.76

Thomas Blunt

Mark Sharp

In the south western part of the churchyard will be found an interesting piece of artistic carving on the grave of Mark Sharp, who died in 1747. He was a carpenter, and before he died it is said that he himself carved all the tools of his trade on his footstone.77 A photo by Kate Hickmott can be seen on the link below:

The Finnish Memorial

A most striking memorial is that to the memory of the Finns who were taken prisoner in the Crimean War when the Russian fort of Bomarsund in the Baltic was captured by the British and French. They were brought to the old Naval Prison in Lewes not far from the church, and many died, probably of tuberculosis.

The memorial was put up by the Czar of Russia (of which Finland then formed part) in 1877, and restored by the Soviet Embassy in 1957 at the request of the Friends of Lewes. In 2013 it was further restored with funding from the Russian and Finnish Governments and a Finnish charity. It is designated by Historic England as a Grade II listed building.78

Finnish Memorial in Churchyard (Photo by Andrew Goodwin)

Charles Dawson

Charles Dawson (1864-1916) was a British amateur archaeologist who claimed to make a number of important archeological and paleontological discoveries. The most famous of these was Piltdown Man, which he presented to the Geological Society in 1912. On the strength of these various discoveries he was elected a fellow of both the Geological Society of London and the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Debate regarding the authenticity of his finds was robust even during his lifetime. He died prematurely in 1916 at Lewes, but it wasn’t until 1953 that Piltdown Man and many of his other finds were proved conclusively to have been been forgeries.

Grave of Charles Dawson, who claimed to have discovered the Piltdown Man (Photo by Susan Harris)

Lt Geoffrey Hotblack

Lt Hotblack of the Essex Regiment was serving in Ireland during the Irish War of Independence in 1921, when he and 6 others were killed in the Crossbarry Ambush – one of the largest battles of the Irish War of Independence. A large body of British troops attempted to encircle about 100 IRA men, and Lt. Hotblack and 6 others were attacked before the British troops had time to respond. Lt. Hotblack died later as a result of gunshot wounds.79

Lt Geoffrey Turner Hotblack grave

CHURCH SCHOOLS

Revd Perfect was very active in matters of children’s education and it was largely due to his exertions that the St John’s Church of England School in St John Street was opened in 1871.

St John’s School, St John Street

The Pells Church of England Primary School then opened in 1896 in Talbot Terrace, again largely due to the efforts of Revd Perfect.80

The old Pells School in Talbot Terrace

St John’s School was subsequently closed in 1938, and many of the remaining pupils transferred to the Pells School.

In 1974 a new Pells Infants department opened on the Landport Road site, and this was joined by the Junior department in 2000 when the Talbot Terrace site was sold to Lewes New School.

Pells C of E Primary School on Landport

The combined Pells School was then much-valued for a further 17 years. Sadly however, in 2017 it was closed by the County Council because – under changed national policies which favoured larger primary schools – it was considered to be no longer viable.

THE CHURCH HALL

The Church Hall in Talbot Terrace was built in 1912, and it has been an important part of church and local community life ever since that time.

Church Hall, Talbot Terrace

In 1940 the Church Room (as it was then called) was used by school children evacuated from Croydon during the war.

In the 1970s, following an upgrade to the kitchen facilities, it was used by the Pells Primary School for school dinners.

Throughout its life it has been used extensively by the church for social events, and at particular times it has served as a meeting place for Sunday School classes and Parent and Toddler groups.

In addition, it has been extensively used as a venue for a wide variety of local community groups.

RECENT DISCOVERIES IN THE CHURCHYARD81

As part of the repair project in 2017, it was necessary to lay drainage pipes in the churchyard across the footprint of the ancient church.

As noted previously, the floor level had been raised in 1779 using filling material from the eastern mound.

The drainage excavation cut through this filling material.

Arrangements were made for a watching brief to be carried out by Archaeology South-East during this excavation, and a number of finds were made during the work.

These finds would suggest that builders’ debris arising from the 1779 alterations was probably thrown in with the filling material from the mound.

Some of the items found are shown here:

48 items of brick, tile and mortar were recovered, displaying a wide chronological mix. The earliest appeared to be late medieval.

The edges of the tile shown here are slightly bevelled, with the top face slightly larger than the bottom. This made it easier for the tiles to be butted tightly together.

Floor Tile , Unglazed

This is a complete iron tool – probably a woodworking tool called a reamer, used to enlarge previously bored holes. It has a solid, square sectioned ‘blade’ and a thinner tang which would originally have been fitted with a cross handle.

Woodworking Tool – Reamer

This fragment of statuary is considered to be part of a large religious sculpture – possibly of John the Baptist, the patron saint.

The stone used has been identified as alabaster – a soft white stone which was particularly popular for carved devotional figures during the 14th-16th centuries in England.

The carving shows part of a right foot (toes missing) with adjacent dark blue and golden drapery. The reverse side of the piece is relatively flat, with a rough finish. This suggests that the fragment was part of a larger carved panel or frieze, rather than a fully three dimensional figure.

Statuary Fragment

As a result of recent pigment analysis,82 the gold, blue, green and flesh tones identified on the fragment are consistent with those found on other English medieval alabasters. Painted and especially gilded decorative stones recovered from archaeological excavations are quite rare, because the original pigments have seldom survived the centuries.

What circumstances brought it to where it was found?

As mentioned previously, the 1779 alterations were considered to be a “destructive reparation”, from which “brasses, stained glass and anything movable” suffered. It seems likely that the statuary of which this fragment was a part may have been one of the casualties of this “destructive reparation” – the broken pieces being thrown in with the filling material used to raise the nave floor. Which raises the question, where are the remaining pieces?!

Combed Staffordshire slipware

Slipware is created by dipping the object in pale slip (a mixture of clay suspended in water, with lead based glaze applied on top) then trailing other colours of slip over the top in sometimes intricate patterns. The technique was first introduced in the late 17th century.

28 items of stone were recovered, which included Purbeck marble, West Country roofing slate, Horsham stone roofing slabs, Hastings Beds sandstone and Caen stone. A wide chronological mix was represented, ranging from late 12th century to 18th century, and reflected building debris from different periods arising from the 1779 alterations.

This block of Caen Stone is likely to be of post-Conquest date. It is double chamfered with a 30mm deep rebate cut into one of the chamfered faces. The surfaces show fine oblique tooling.

Caen Stone

RECENT DISCOVERIES BENEATH THE PRESENT CHURCH83

As part of the interior remodelling project in 2017, it was necessary to excavate for column foundations to support the new west gallery and the proposed north-east stairs. Arrangements were made for a watching brief to be carried out by Archaeology Services Lewes during this excavation.

A number of finds were made during this work, the earliest being an unstratified prehistoric flint flake and a single piece of Roman flue tile.

38 items of pottery were recovered. The earliest were two sherds of late Anglo-Saxon Coarse Flinty Ware (c. 850-1050), one of which is shown here.

Late Anglo-Saxon Coarse Flinty Ware (c.850-1050)

Most however were cooking pot sherds of Saxo-Norman Lewes Flinty Ware (c.1050-1200). These, together with other finds on the site, suggest an intense level of activity at this time.

A small number of metalwork items were recovered, probably Medieval or Post-Medieval. These included fragments of iron nails and window lead strip. The most interesting however was a fragment of copper alloy strip, with cut-outs creating a wave pattern, filled with what appears to be jet.

Copper Alloy Strip (Post Medieval)

Miscellaneous finds included two clay tobacco pipe stem fragments which have 1.86mm and 2.27mm bore holes. This would suggest a date range between the early 18th to mid-18th century

Clay Pipe Stem Fragments (18th-19th Century)

50 marine molluscs were recovered from the excavations underneath the floor of the church. Most were fragmented Oyster shells with few worm infestations, indicating the likely source of these molluscs was from purposely farmed oyster beds or ponds.

Oyster Shell Fragment

REFERENCES

Abbreviations used: SAS (Sussex Archaeological Society); SAC (Sussex Archaeological Collections); SNQ (Sussex Notes and Queries); SRS (Sussex Record Society)

Sources

A History of the County of Sussex (1940) London, Victoria County History

Bleach, J. (1997) SAC 135

Brent, C. (2004). Pre-Georgian Lewes. Lewes: Colin Brent Books

Davey, L.S. (1933) The Church of St John sub Castro, A Historical Record. SAS Library

Field, Revd R. (2006) Ten Centuries of History: The Story of St John sub Castro, Lewes

Fisher, E.A. (1970) The Saxon Churches of Sussex, Newton Abbot, David & Charles

Gilbert, R(1969) The Old Church of St John sub Castro, SAS Library, Barbican Hse, Lewes

Harris, R.B. (2005) Lewes Historic Character Assessment Report

Lambert, P. The Painters Lambert of Lewes https://familylambert.net/james-lambert.html

Lambeth Palace Library, Lewes, St John sub Castro (1827-1840) ICBS00850, a,b,c

Leigh’s New Picture of England and Wales (1820) London, Samuel Leigh

Lewes District Council (2007) Lewes Conservation Area Appraisal

Nairn & Pevsner, (1965) The Buildings of England/Sussex, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books

PBN Publications. (1988). 1831 census. St. John Sub Castro, Lewes, Sussex.

Shapland, M (2019) St John’s early sculpture and chancel footings, Archaeology South-East

Citations referred to in the above include the following:

Byng, J. (1788) Diary of a Tour through Sussex, Brighton and Hove Library Service

Camden, W (1586), Britannia, Sussex

Elliot, J. (1770) Folio manuscript book in SAS Library

Elliot, J. Letter to Sussex Advertiser, 16th January 1775

Glynne, S. SNQ May 1964; Sussex Church Notes of Sir Stephen Glynne (Parsons)

Goring, J. (2003) Burn Holy Fire, Cambridge, Lutterworth Press

Grose, F. (1793) The Antiquities of England and Wales, Hopper

Holman, G (1905) Some Lewes Men of Note, Lewes, Baxter

Horsfield, Revd T.W. (1824) The History and Antiquities of Lewes, Lewes, Baxter

Lower, M.A, (1865) The Worthies of Sussex

Luxford, J. (2005) Church Monuments vol 20 31–39 citing Thomas Anlaby.

Manning, R.B (1969) Religion and Society in Elizabethan Sussex, Leicester Univ. Press

Parish Registers; Vestry Minutes 1779, 1883; St John sub Castro, The Keep

Pye, D.W. The Magnus Inscription SNQ Vol XVI no.6

Rouse, J. (1825) Beauties of Sussex, Rouse

Rowe, J. (1928) The Book of John Rowe, Sussex Record Society (SRS) 34

Sussex Record Society, L, p59

Taylor, S. (1663) The History of Gavel-kind etc, London, Starkey

Terrier (1635), St John sub Castro, SAS Library

Wakeham, T. (1783) Copy of The Book of John Rowe with additional drawings and notes.

Images

Unless otherwise noted, photos are by Stuart Billington

For a list of the Rectors84 since 1324 click: RECTORS OF ST JOHN SUB CASTRO

Early morning sun filtering into the eastern end of St John’s Churchyard (Photo by Susan Harris)

Copyright TRINITY Church Lewes PCC 2019

Comments about this page

Excellent information and photographs, very interesting.

Add a comment about this page